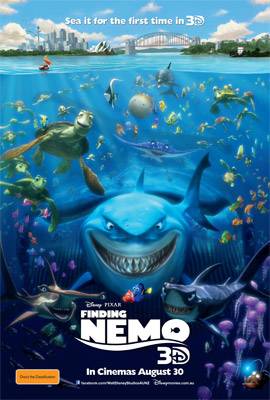

Finding Nemo 3D

Finding Nemo 3D

Cast: Albert Brooks, Ellen DeGeneres, Alexander Gould, Willem Dafoe, Brad Garrett, Allison Janney, Austin Pendleton, Joe Ranft, Geoffrey Rush, Andrew Stanton, Elizabeth PerkinsDirector: Andrew Stanton

Genre: Comedy, Animated, Adventure

Rated: G

Running Time: 104 minutes

Synopsis: "Just keep swimming? just keep swimming? just keep swimming, swimming, swimming." - Dory

"Finding Nemo" returns to the big screen-for the first time ever in thrilling Disney Digital 3D&trade-introducing a whole new generation to the stunning underwater adventure. Director Andrew Stanton, a two-time Oscar® winner for "Finding Nemo" and 2008's "WALLoE," says that the 3D version of the film is breathtaking-literally. "Watching the first few scenes from 'Finding Nemo' in 3D was like I'd never seen a 3D movie before," says Stanton. "It took my breath away. It felt like I was more underwater. It makes the scary moments scarier. It makes the beautiful moments more beautiful. It really drops you deeper into the story. It just amplifies everything."

Teeming with memorable comedic characters and heartfelt emotion, "Finding Nemo" follows the momentous journey of an overprotective clownfish named Marlin and his young son Nemo--who become separated when Nemo is unexpectedly taken far from his ocean home in the Great Barrier Reef to a fish tank in a dentist's office. Buoyed by the companionship of Dory, a friendly-but-forgetful blue tang, Marlin embarks on a dangerous trek and finds himself the unlikely hero of an epic journey to rescue his son--who hatches a few daring plans of his own to return safely home.

"Finding Nemo" won the 2003 Academy Award® for Best Animated Feature the film was nominated for three additional Oscars (Best Writing, Original Screenplay Best Music, Original Score Best Sound Editing). It was also nominated for a Golden Globe® Award for Best Motion Picture-Comedy or Musical. In 2008, the American Film Institute named "Finding Nemo" among the top 10 greatest animated films ever made. At the time of its release, "Finding Nemo" was the highest grossing G-rated movie of all time. It remains the fifth highest grossing animated film worldwide.

"'Finding Nemo' was an amazing film to work on and it exceeded our expectations at every step of the process," says producer Graham Walters. "Throughout the production, people on the crew would walk into the dailies and be blown away by what they were seeing."

With an Oscar®-nominated screenplay by Stanton, Bob Peterson and David Reynolds, "Finding Nemo" is co-directed by Lee Unkrich, who went on to direct the Oscar® -winning "Toy Story 3." John Lasseter is the executive producer. Award-winning composer Thomas Newman ("The Help," "WALL-E") contributed an exciting and sophisticated score that earned him an Oscar® nomination, among other nominations and awards.

"'Finding Nemo' is the perfect movie in 3D," says Lasseter, who creatively oversees all films and associated projects from Walt Disney and Pixar Animation Studios. "We didn't realise it when we made it originally. Every scene has what we call particulate matter in the water to give it a sense of place. When you see that in 3D, it's unbelievable. There's so much depth. From the layers and layers of coral reef to the rows of teeth in Bruce the shark's mouth, it's absolutely amazing."

Release Date: August 30th, 2012

A Whole New Dimension

Filmmakers Invite Audiences to Dive Deeper with Stunning 3D ImageryThe underwater setting of "Finding Nemo" required a great deal of research and experimentation to achieve the spectacular look filmmakers wanted to capture in the original 2D film. But, it turns out, the pieces put into place so many years ago actually set the stage for a rather brilliant 3D realisation.

"I can't imagine a movie better suited for 3D," says director Andrew Stanton of "Finding Nemo." "Firstly, there's something hyper dimensional about computer animation that's interesting even when it's on a 2D plane. Secondly, this movie is set in an environment that has a very definitive three-dimensional quality to it-being underwater is like being in a big cube, there's space on all sides. We had to introduce all these elements-light shafts, particulate matter, changes in the current-to remind the audience of that space. It turns out that those tricks were a huge aide in incorporating the 3D effect. It's as if we planned for it."

Joshua Hollander, who directed the 3D production of "Finding Nemo," says that like lighting, camera angles, colour or texture, 3D is a tool they use to support the story. "Our goal always is to honour the original film. We seek to create a captivating and rewarding 3D experience that takes the audience even deeper into the emotional aspects of the film."

According to stereoscopic supervisor Bob Whitehill, Pixar Animation Studios has a clear philosophy when it comes to 3D. "When we approach 3D, we often think of what we call the three Cs," says Bob Whitehill. "First off, we want to make it comfortable, so it's easy to watch. Secondly, we want to make it consistent with the original vision of the film-so if Nemo is meant to feel trapped in a small space in the tank in the dentist's office, we need to make it feel small in 3D, too. Thirdly, we want to make it captivating. We want to bring a new world to the audience. If they've gone out of their way to see 'Finding Nemo' in 3D, we want to make it more immersive than ever and pull them into this world in a new and different way."

The 3D team begins the effort by pulling the original assets, which according to Joshua Hollander, must be converted to today's technology and copied to preserve the original film. Then they do what's called triage, in which each shot is evaluated and made to look like the original. Like opening an old word processing document with new software, today's technology-while superior-can't translate every aspect of the original. "Many problems can occur as a result of changes in software or systems infrastructure, location of files or missing files, and that sort of thing. Not everything matches the original or even renders correctly. A big part of our job is to sweep through the film and fix these sorts of issues," says Joshua Hollander.

That's when the shots are rendered, assembling the components of the animation. "We've re-rendered the entire film at a higher resolution," says Bob Whitehill. "And because in 3D, you see a slightly different view for your left eye than your right eye, you get a brand new, bigger and clearer image to each eye."

Bob Whitehill, who evaluates every shot and determines where each object and character should exist in 3D space, says that while the process might be arduous-it took about nine months to complete-there is a distinct advantage in creating a 3D version of "Finding Nemo" versus a live-action film. "Imagine if you were recreating a movie ten years after it was filmed-getting all the actors back, putting them in the exact same position in an identical set and having them deliver their lines exactly as they did before with the cameras positioned just so-it'd be impossible. But we can do that here because our films are computer generated. It's really not a conversion-we initially filmed 'Finding Nemo' in 2D. This time, we filmed the exact same movie in 3D."

The result? Spectacular-though filmmakers are hard-pressed to pick just one scene that best illustrates the power of 3D. Says Bob Whitehill, "During a sequence we call 'First Day of School' when Marlin brings Nemo out to the reef, you travel along with Mr. Ray and it almost feels like you're scuba diving-you feel like you can reach out and touch the fish swimming by. Seeing it in 3D just heightens that connection to the environment and makes it more powerful."

Adds Joshua Hollander, "Many of the characters are really cool in 3D-Nigel the pelican is fun when his beak plays with the 3D space, and the anglerfish with its little lure. A scene that really surprised me when I first saw it in 3D was the one with the whale's approach. It's a very long, slow shot-Dory is speaking whale and Marlin is doing what Marlin does. The whale approaches camera slowly, the krill swim past and the whale swallows Dory and Marlin. The 3D effect is really cool. I wasn't expecting it."

But it's the jellyfish sequence that left Bob Whitehill in shock. "I was struck by how swept into the story I got," he says. "My job is to evaluate the shots technically and make sure we're doing everything right, but I found myself fighting for our characters. In the jellyfish sequence, Marlin has Dory in his fins and he's looking around for a way out and the camera spins around them. The jellyfish are so bright and beautiful and the 3D is really pumped up at that point. It's a really powerful shot and I think it captures the whole emotion of that scene."

And that's the idea. "The whole point of this movie," says Andrew Stanton, "is the idea of this predatory world-how do you let your kids cross the street alone when you know there are creatures all around that you can't see? How do you deal with that fear? This film in 3D provides us with yet another way to push the audience that much deeper into the story. I can't think of a better application for the technology."

Who's Who in Finding Nemo 3D

Memorable Voices Bring Colourful Cast of Characters to Life

Marlin's journey along the Great Barrier Reef to rescue his son Nemo is filled with a host of colourful underwater characters. Optimistic but forgetful friend Dory joins him on the adventure, which introduces the sheltered Marlin to everything from a trio of sharks practicing a self-help program to a bale of hip sea turtles who know their way around the East Australian Current. Meanwhile, Nemo-snatched from the reef by a diver-finds himself in an aquarium at a dentist's office, surrounded by a group of spectacular saltwater friends known as the tank gang.

The iconic characters and the roster of talented actors that helped make them so memorable are what make "Finding Nemo" a favorite among moviegoers.

Marlin is a fretful and slightly neurotic clownfish father voiced by the acclaimed actor/director/comedian Albert Brooks ("Drive," "This is 40"). He sports just three stripes ("One, two, three-that's all I have?") and for a clownfish, he's not as funny as one might expect. But he's fiercely protective of his son Nemo, wanting to do everything he can to make sure nothing ever happens to him.

Director Andrew Stanton said Albert Brooks was a pro at maximising his scenes. "Even when his character wasn't asked to be funny in a scene, he knew exactly how to play it for entertainment."

Dory is the eternally optimistic and forever forgetful blue tang brought to life by the Emmy®-winning comedian Ellen DeGeneres ("The Ellen DeGeneres Show"), who was nominated for an MTV Movie Award for Best Comedic Performance.

"She brought a real kindness and gentleness to the part, along with rhythm and quirkiness," said Andrew Stanton of Ellen DeGeneres' performance.

What Dory lacks in short-term memory, she makes up for in heart. Always quick to lend a fin, she's the only fish in the sea who offers to help Marlin when his son Nemo is plucked from his ocean home. Dory knows how to party with sharks, play hide-and-go-seek with sea turtles and-fortunately for Marlin-she even speaks whale.

Nemo is an adventurous young clownfish born with a bad fin, though his overly protective father calls it his "lucky fin." After being captured by a diver and dropped in an aquarium, Nemo meets an oddball tank gang who dub him "Shark Bait" and help him hatch a plan to escape back to the ocean to reunite with his dad.

Alexander Gould ("Weeds") was 9 years old when he lent his voice to Nemo, and he "brought a genuine, untainted quality to the voice of Nemo," said Andrew Stanton. "It's amazing how many kids sound prepped or have some preconceived notion of what a good actor should sound like. Alexander Gould sounded real and he totally understood direction. We were really lucky to find him."

Gill is the brooding moorish idol leader of the tank gang who takes newcomer Nemo under his fin. Willem Dafoe ("The Aviator," "Platoon") gave voice to Gill, who-like Nemo-hails from the big blue. He'd give anything to go home.

Bloat is a blowfish with a tendency for emotional as well as literal blow-ups. Voiced by Emmy® winner Brad Garrett ("Everybody Loves Raymond," "Gleason"), Bloat conducts the tribal ceremony officially dubbing Nemo as "Shark Bait" and welcoming him into the tank gang.

Peach is an astute starfish who has her eyes peeled at all times on behalf of the entire tank gang. Allison Janney ("The Help," "Juno") provided the voice for Peach, a perceptive matriarch who keeps a protective eye on Nemo.

Gurgle is a quick-to-panic royal gramma with a fear of germs. He's voiced by film and stage veteran Austin Pendleton ("Wall Street: Money Never Sleeps"). Despite his disdain for dirt, he's all drama when the dentist foils their messy escape plan with a new tank cleaner. "Curse you Aqua Scum!"

Bubbles is a bubble-obsessed yellow tang. Stephen Root ("J. Edgar," "The Conspirator") lent his voice to the effervescent character. "Bubbles! Bubbles! Bubbles!"

Deb and Flo is a reflective blue-and-white humbug damsel fish who believes her reflection is her twin sister. Voiced by Vicki Lewis ("How I Met Your Mother"), Deb is always in touch with her "twin sister" Flo, who is always there when Deb needs her. But Deb secretly doubts Flo's mental capacity-"She's nuts."

Jacques is a fastidious cleaner shrimp. Late Pixar storyman Joe Ranft ("Toy Story 2" as Wheezy, "A Bug's Life" as Heimlich the caterpillar) gave Jacques a debonair French accent. "Voila! He is clean."

Coral is Nemo's mom who meets an unfortunate fate. Elizabeth Perkins ("Weeds") gave voice to Coral.

Crush, the unflappable sea turtle voiced by director Andrew Stanton, is the ultimate laidback dad that throws Marlin for a loop. Crush's biggest fan is offspring Squirt who agrees with his dad that almost everything is awesome and righteous.

Mr. Ray is a musical manta ray teacher. Pixar veteran Bob Peterson, one of the screenplay writers for the film, provided Mr. Ray's popular pipes, known for clever, rhyming songs like, "Seaweed is cool. Seaweed is fun. It makes its food from the rays of the sun."

Bruce is a great white shark who desperately wants to stop eating fish. Voiced by Barry Humphries (Dame Edna Everage), Bruce holds meetings for he and his shark companions to share their problems and practice their motto-"Fish are friends, not food." Bruce's vegetarian efforts get derailed when a minor injury to Dory changes his friendly demeanor.

Anchor is a soft-hearted hammerhead shark who believes a group hug can help his shark pals' problems.. Eric Bana ("The Time Traveler's Wife") lent his voice to Anchor.

Chum is the hyperactive mako shark who "misplaces" his fish friend. Bruce Spence provided his voice.

Diving In

How "Finding Nemo" Came to Be

The story of "Finding Nemo" was very personal for director/writer Andrew Stanton, derived from a series of events in his own life. A visit to Marine World in 1992 started him thinking about the amazing possibilities of capturing an undersea world in computer animation. This was three years before "Toy Story" made its debut, but Andrew Stanton was fascinated with the prospect of creating such a wondrous environment. Another piece of the puzzle came from Andrew Stanton's childhood memories of a fish tank in his family dentist's office. He recalled looking forward to going to the dentist just so he could look at the fish. Andrew Stanton remembered thinking, "What a weird place for fish from the ocean to end up. Don't these fish miss their home? Would these fish try to escape and go back to the ocean?"

The final piece of the puzzle for Andrew Stanton was his own relationship with his son. He explained, "When my son was five, I remember taking him to the park. I had been working long hours and felt guilty about not spending enough time with him. As we were walking, I was experiencing all this pent up emotion and thinking 'I-miss-you, I-miss-you,' but I spent the whole walk going, 'Don't touch that. Don't do that. You're gonna fall in there.' And there was this third-party voice in my head saying 'You're completely wasting the entire moment that you've got with your son right now.' I became obsessed with this premise that fear can deny a good father from being one. With that revelation, all the pieces fell into place and we ended up with our story."

Pitching the story to his mentor and colleague John Lasseter was the next step in "Nemo's" evolution. Andrew Stanton prepared a roomful of elaborate visual aids and launched into a pitch to sell his story idea. After an hour, an exhausted Andrew Stanton asked John Lasseter what he thought. "You had me at 'fish,'" John Lasseter replied.

John Lasseter recalled, "Andrew Stanton had this great little drawing over his desk which showed two small fish swimming alongside a giant whale. And I always liked that. He told me it was something he was thinking about but I didn't hear anything more about it until the pitch. I've been a scuba diver since 1980 and I just love the underwater world. When he pitched this idea, I knew that it was going to be amazing in our medium. We always pride ourselves at Pixar on matching the subject matter of our movies with the medium. I really did know when he said 'fish' and 'underwater' that this film was going to be great.

"Andrew Stanton is such a great storyteller," added John Lasseter. "He has an absolute fantastic devotion to making sure that the movie is not predictable. He's always added that to all of our films and I've learned a lot from him in that area. He believes that if something is getting too schmaltzy, he has to turn it on its ear. He has a way of getting sincerity through insincerity, but it's not so insincere that it doesn't have heart. He tends to be a little cynical but, in the end, there's so much heart underneath what he's doing."

Andrew Stanton concluded, "Telling a story where the protagonist is the father got me excited. I don't think I've ever seen an animated film from that perspective. It made me interested in wanting to write it because I knew I could tell that story. I also thought that the ocean was a great metaphor for life. It's the scariest, most intriguing place in the world because anything can be out there. And that can be a bad thing or a good thing. I loved playing with that issue and having a father whose own fears of life impede his parenting abilities. He has to overcome that issue just to become a better father. And having him in the middle of the ocean where he has to confront everything he never wanted to face in life seemed like a great opportunity for fun and still allowed us to delve into some slightly deeper issues."

He added, "My dad gave me some good advice about parenting. He said, 'The tough choice you have is you can either be their parent or their friend. Pick one.' It's a lifelong dilemma and I love indulging in that truth with this film. I'm considered the most cynical of the group here at Pixar. I'm the first one to say when something is getting too corny or too sappy. Yet, I'd say I'm probably the biggest sucker romantic in the group, if the emotion is truthful. I just loved the idea of doing a father-son love story. They're in eternal conflict."

Gone Fishin'

Pixar's Animators Draw Inspiration from a Fish Expert and a Tankful of Fish

It's all about the research when it comes to developing the kind of story-driven films for which Pixar Animation Studios is known. For "Finding Nemo," visits to aquariums, diving stints in Monterey and Hawaii, study sessions in front of Pixar's well-stocked 25-gallon fish tank, and a series of in-house lectures from an ichthyologist all helped to get filmmakers into the swim of things.

The team also looked at some of the Disney classics that involved underwater scenes-"Pinocchio," "The Sword in the Stone," "Bedknobs and Broomsticks" and "The Little Mermaid"-for inspiration. In the end, it was the naturalistic portrayal of animal life in "Bambi" that left the biggest impression.

Andrew Stanton explained, "We kept coming back to 'Bambi' because of the way the filmmakers adhered to the real nature of how these animals moved and what their motor skills were. They used that as the basis for getting as much expression, activity and appeal. We wanted our characters to work in that same way. We thought of it as 'Bambi' underwater."

Supervising animator Dylan Brown and directing animators Alan Barillaro and Mark Walsh (director of Pixar's new short "Partysaurus Rex") were responsible for guiding the animation team. With a large cast of characters-ranging in size from the petite cleaner shrimp, Jacques, to the enormous blue whale-this group had their work cut out for them as they learned about fish locomotion and discovered how to create believable behaviours for characters without arms and legs.

"Each film has its own unique set of challenges and we always begin by trying to figure out what they are and how to solve them," said Dylan Brown. "With 'Nemo,' we had an entire cast of fish characters with no arms or legs. Since they didn't have the traditional limbs to allow strong silhouettes, we had to invent a whole new bag of tricks. In the beginning it was a bit daunting and frustrating. We began analysing what was appealing in terms of posing fish. We put a lot of work into the face and getting the facial articulation just right. We didn't want them to be just heads on sticks like in a Monty Python sketch. Their faces had to be integrated with the entire body language. Where a human character might just turn his head to look at something, a fish might turn his head just a little and the entire body would pivot along with it."

In the past, animators were always told to "ground their characters" and avoid letting them "float." With "Finding Nemo," they had to figure out the exact opposite-how to make them look like they were floating, but in water-not air.

Alan Barillaro said, "It became fun and challenging to come up with a whole new range of how to communicate and gesture. You don't have gravity to deal with underwater, so we discovered things like when a character gestured, he would tend to drift a bit more. I found that a lot of the gestures humans make could be boiled down to eye and face movements. I would look at my own face in the mirror and imagine I had a tail on the back of it."

Mark Walsh recalled, "The first thing that Andrew Stanton did on the film was to sit with us in front of the fish tank and basically pitch the story to us. He explained that the magic of the world was going down to the perspective of a clown fish and imagining him going through an entire ocean and encountering sharks, turtles, jellyfish, etc. You imagine moving in closer and seeing this little fish and how hard he is trying."

Helping the animators get up to speed on fish behaviour and locomotion was Adam Summers, a noted professor in the Ecology and Evolution department at the University of California at Irvine. "I'm what is called a biomechanic or sometimes a functional morphologist," said Adam Summers at the time of the film's release. "My specialty is applying simple engineering principles to how animals move and eat. They asked me to come in and talk about things like fish shapes and colours, and I ended up teaching an essentially graduate-level ichthyology course to the Pixar staff. There were at least 12 lectures. It was really an incredibly rewarding thing because I found that these folks like their job as much as I like mine. They were infinitely curious about fish and they were flat-out the best students I had ever had."

Adam Summers also gave the character designers and animators some important insights into fish locomotion by explaining the difference between flappers and rowers. Clownfish are rowers who tend to propel themselves by moving their pectoral fins in a horizontal motion. At higher speeds they wiggle their entire body. Blue tangs, like Dory, are flappers, who flap their fins up and down to move and almost never wiggle their entire body. The result was that Marlin's movements were more fluid and graceful, while Dory tended to flit sharply about."In most animated films with fish," said Adam Summers, "the characters move back and forth with no visible propulsive device and that really offends the eye. You don't need to be an ichthyologist to know there's something wrong with that kind of locomotion. It'd be like watching a horse trot with two of its legs still. In 'Nemo' if a fish is moving, its fins are moving. There's a sort of kinetic feel to the characters that tells you they're underwater. They're not acting in air. When they flap around, it has consequences for their whole bodies."

Technical Triumphs

A New High Water Mark for Computer Animation

Water has traditionally been one of the most difficult things to create effectively and economically in computer animation. Faced with a film that was set largely underwater, the technical team on "Finding Nemo" had to find new ways to meet the enormous demands of the production and solve some of the problems that had been encountered by others in the past. Supervising technical director Oren Jacobs led the effort to give Andrew Stanton and his team exactly what they wanted.

"Our starting point was to watch a lot of films with underwater scenes and analyse what made them seem like they were underwater," explained Andrew Stanton. "What made them not seem like they were in air? It was a bit like getting a great cake and trying to figure out how somebody baked it by breaking it down. We came up with a shopping list of five key components that suggest an underwater environment-lighting, particulate matter, surge and swell, murk and reflections and refractions."

Oren Jacob added, "Even before we had a finished script, we knew we had a story about fish in a coral reef. That was enough for our global technology group to begin coming up with tools for making water move back and forth. Early on, we took a diving trip to Hawaii with some of the film's key players. Then we looked at every Jacques Cousteau, National Geographic and 'Blue Planet' video we could find. We also studied every underwater film to understand what the filmmakers chose to caricature. We came up with our own idea of what audiences expect to see with water and developed our own ratios and proportions."

Under Oren Jacob's supervision were six technical teams specialising in different components and environments seen in the film. Lisa Forssell and Danielle Feinberg were the CG supervisors responsible for the Ocean Unit. David Eisenmann and his team handled the models, shading, lighting and simulation for the Reef Unit. Steve May headed up the Sharks/Sydney Unit, which tackled the submarine scene, shots inside the whale and most of the above-water scenes in the Harbor. Jesse Hollander oversaw the Tank Unit, which created all the elements for the fish tank. Michael Lorenzen was in charge of the Schooling/Flocking team, which created hundreds of thousands of fish plus key elements for the turtle drive sequence. Brian Green led the Character Unit, which created the look and complex controls for nearly 120 aquatic, bird and human characters.

The Ocean Unit was responsible for such scenes as the school of moon fish, the angler fish chase and the turtle drive in the East Australian Current. The unit's most challenging and impressive scene, however, was the jellyfish forest. This rich and colourful moment finds Marlin and Dory in an ever-expanding and increasingly dangerous sea of deadly pink jellyfish.

Lisa Forsell explained, "This scene involved several thousand jellyfish. Our unit built the model for a single jellyfish and put a lot of work into the build-up of jellyfish density. This involved creating a simulation for the group that controlled the movement of the tendrils, how quickly they swam and in what direction. We had some great reference footage and were particularly fixated on one species from Palau that we found at the Monterey Aquarium. David Batte wrote a whole shading system we called 'transblurrency.' Transparency is like a window and you can see right through it. Translucency is like a plastic curtain that lets light through but you can't see through it. Transblurrency is like a bathroom glass you can see through it but it's all distorted and blurry."

For David Eisenmann and his team on the Reef Unit, the challenge was to create a caricatured version of the coral reef. They were responsible for the film's rich and vibrant opening scenes and building the anemone home of Marlin and Nemo. "Our group started with a realistic approach to the reef," he said. "The director wanted about 30 percent of whatever you see on the screen to be moving to make it feel like it was underwater. For the reef scenes, this meant simulating movement for sponges, moss, grass and other kinds of vegetation.

"The reef is very stylised and almost dream-like," continued David Eisenmann. "The colour palette opens with purples and blues and jumps to vibrant reds and yellows. There is a real storybook, fantasy quality to it. As the story progresses to the drop-off, things become more real and less colourful. Because this is a journey film, our main characters travel quite a distance through the reef. Our modelers were able to keep the reef scenes interesting and exciting by mixing together different shapes and textures. We had a whole grab bag of vegetation we could use to populate a scene and, by putting different textures and shaders onto the catspaw and staghorn coral and the sponges, we could make it feel like completely different models from scene to scene. We spent about a year researching corals and sponges. In the end, we were able to take one basic form of sponge and shape, shift and mold it into more than 20 variations."

"Instead of building a reef set and flying a camera around, David Eisenmann and the Reef Unit had an amazing system for building the reef on a shot-by-shot basis," explained producer Mark Walters. "They had an entire nursery of coral, plant life, etc. that they could throw together in different configurations and custom sculpt each shot for the needs of the story. They did an amazing job."

Picking up where the Reef Unit left off was the Sharks/Sydney Unit, under the direction of Steve May. This group took on a wide variety of scenes with diverse locations, including the fishing net scene with hundreds of thousands of grouper fish, the scene inside the blue whale, all of the shots in Sydney Harbor the submarine set where the sharks meet.

Steve May explained, "The submarine is supposed to be like a haunted house. It's very spooky and creepy. There are nearly 100 mines surrounding the sub and we worked hard to cover them all with moss and have them move with the surge and swell of the ocean. Inside the sub, it's supposed to feel very tight all the time. It's crammed full of knobs, valves and pipes. Because we had our own layout and modelling people, we were able to quickly build and dress the sub as we went. We knew what we needed and built customised parts along the way."

One of the big challenges for Steve May and his team was simulating the splashing water inside the blue whale. "Pixar really hadn't done splashing water before," said Steve May. "We had to figure out a way to do three-dimensional water, develop the software and new techniques for running simulations to compute the motion of the water, and then render it to look realistic. And the entire time, the whale is swimming and going up and down. Mark Water had to explode and splash all around as the whale's giant tongue lifts Marlin and Dory out of the water. This was a whole different water dynamic than the film's underwater scenes, and we had to allow for the large-scale behaviour of the crashing water and the very small detailed behaviour of our two fish characters. Those different resolutions were very difficult to accommodate. Lighting that scene was probably the hardest thing we've ever had to light because the entire set was moving, organic and filled with splashing water."

Jesse Hollander and the Tank Unit were responsible for all of the lighting, modelling, shading and rendering associated with the dentist's office and the fish tank. Creating the tank itself and dealing with issues of reflection and refraction were a major challenge for this resourceful group. They also built a wide range of set pieces for their scenes ranging from dental equipment to the tiki heads and volcano in the tank, plus nearly 120,000 pebbles on the tank floor.

"One of the biggest things that our unit had to develop for this film was the reflections and refractions connected with the tank," recalled Jesse Hollander. "Our starting point was the actual physics of what happens to light when it enters not just water, but a glass box filled with water. This meant computing for glass, then water, then glass into water. But in our movie, we're not dealing with just physics, we need to be able to have control over those physics. Most of the time we were able to achieve the effect we wanted by offsetting the camera. At certain angles inside the tank, there is something called TIR-total internal reflection-where the glass becomes a perfect mirror. We play off this quite a bit with the characters of Deb and Flo. At other angles, the view from the tank shows double imagery. Whenever we're inside the tank, we always use reflections. Refractions become more of a selective thing and we only use them where necessary."

As with all Pixar films, attention to detail was critical. Jesse Hollander explained, "As far as the objects in the tank, we tried to give them a very cheap, kitschy Vegas feel-lots of colour and cheap plastic. We went to a lot of effort building fake moulding lines and flashing for the plastic items."

Another key contributor to the film's overall technical advances was Michael Lorenzen, who oversaw a group of animators and technicians in the Schooling/Flocking Unit. This unit helped to create spectacular crowd scenes that included tens of thousands of fish. They also populated the turtle drive sequence with nearly 200 background turtles.

The Look of Finding Nemo

Production Design, Cinematography and Lighting Complete the Picture

Overseeing the production design for "Finding Nemo" was Ralph Eggleston, a Pixar veteran who directed the studio's Oscar®-winning short "For the Birds" and went on to serve as production designer for "WALL-E." He prepped for his role on "Nemo" with several diving trips and a visit to Sydney Harbor to get the lay of the land and sea. The film's two directors of photography-Sharon Calahan and Jeremy Lasky- brought their expertise to the areas of lighting and layout, respectively, to help capture Andrew Stanton's vision for the film on screen.

"One of the biggest decisions we had to make was how much to caricature reality," said Ralph Eggleston. "Fish have an almost caricatured shape to begin with and Andrew was fairly adamant that he didn't want to overly anthropomorphise the characters. And so we actually had to go the other way and bring the world closer to the caricatured nature of the fish. If we put these fish in anything that looked even quasi-real, it wouldn't work. The characters and the world had to be on a parallel track.

"One of our first priorities was to make the fish seem appealing," he continued. "Fish are slimy, scaly things and we wanted the audience to love our characters. One way to make them more attractive was to make them luminous. We ultimately came up with three kinds of fish-gummy, velvety and metallic. The gummy variety, which includes Marlin and Nemo, has a density and warmth to it. We used backlighting and rim lights to add to their appeal and take the focus off their scaly surface quality. The velvety category, which includes Dory, has a soft texture to it. The metallic group was more of the typical scaly fish. We used this for the schools of fish."

Ralph Eggleston and Sharon Calahan shared a love for the soft, bright Technicolor films of the 1940s and had frequently discussed making a CG animated film that looked like it was from that period of time. With "Nemo," they got their chance. The underwater setting lent itself to soft backgrounds and characters with a glow around them.

Ralph Eggleston said, "'Nemo' doesn't look like a three-strip Technicolor film, but rather a modern version of the quality you could achieve with this process. Another big inspiration for us was Disney's 'Bambi.' It's a very impressionistic film. Things fall off in the backgrounds, and you focus on the characters. That's the approach we adopted. The film begins with an intense Garden of Eden coral reef. From there, the underwater backgrounds tend to become more impressionistic with just a mountain or sandy bottom in view."

"A big part of our job was creating believable underwater environments," said Sharon Calahan. "And that took on many forms since we had clear water, super-murky water and even water in a fish tank. We had to figure out the common elements so that stylistically we could tie them all together."

Sharon Calahan credited Andrew Stanton with "having an amazing eye for forms and designs. Design themes and strong graphic elements are really important to him and he really gravitates towards them-which is great because it creates a strong visual structure for the film. He's also a lot of fun to work with because he is willing to take some risks and experiment. Andrew Stanton also took a real interest in what lighting could do to plus the emotional content of the movie."

Thomas Newman's Score and Gary Rydstrom's Sound Effects Add Authenticity

Music and sound effects are integral parts of any motion picture experience and the filmmakers at Pixar have always used these elements to maximum advantage. With "Finding Nemo," director Andrew Stanton collaborated with composer Thomas Newman and multiple Oscar®-winning sound designer Gary Rydstrom.